General Caption: Big Bang nucleosynthesis (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m) is a key element of Big Bang cosmology. The fact that calculated Big Bang nucleosynthesis is in agreement with observation (except to a degree for the cosmological lithium problem) is a key verification of said Big Bang cosmology (see below Image 6 Caption).

The situation is also reciprocal in that other verified elements of Big Bang cosmology lead us to believe calculated Big Bang nucleosynthesis is right. In fact, all well established grand theories or paradigms (as Big Bang cosmology is) are based on a network of mutually supporting verifications which gives them strong credibility.

- General Features:

- The

Big Bang nucleosynthesis era

(cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m)

began at ∼ 10 s after the

fiducial cosmic time zero (i.e., t=0,

lookback time 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018)))

of the Friedmann equation (FE) models.

At cosmic time ∼ 10 s,

the cosmic temperature

had fallen sufficiently low that

protons and

neutrons

were NO longer being created by

pair creation

by photons

(since the photons NO have

the energy as the

required

photon energy E=hν as

cosmic temperature falls

to create such massive particles)

and nuclei

were NO longer being destroyed by

photodisintegration

(since the photons NO longer have

the photon energy E=hν as the

cosmic temperature falls

to destroy nuclei).

Also by some asymmetry in the early part of

early universe

(cosmic time (10**(-12) s -- 377700(3200) y),

the bulk antimatter had vanished

(Wikipedia:

Antimatter: Origin and asymmetry;

Wikipedia: Baryogenesis).

So there was NO longer antimatter

to complicate

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

at cosmic time ∼ 10 s.

- Big Bang nucleosynthesis

is the nucleosynthesis

(i.e., creation) of

the light

elements

and isotopes thereof

(i.e., hydrogen (H),

deuterium (D, H-2),

helium-3 (He-3),

Helium-4 (He-4),

lithium-6 (Li-6)

(very little of this),

lithium-7 (Li-7))

of the

primordial cosmic composition (fiducial values by mass fraction:

0.75 H, 0.25 He-4, 0.001 D, 0.0001 He-3, 10**(-9) Li-7)

(which to a large degree is the

cosmic present = to the age of the observable universe = 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018)

composition of the

intergalactic medium (IGM)

of the observable universe.

To be more precise,

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

produced overwhelmingly most of the modern

cosmic abundances

of hydrogen,

deuterium

(of which the nuclei are

called deuterons),

and helium,

and some significant part or maybe almost all of the

cosmic abundance

of lithium.

Big Bang nucleosynthesis (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m) occurred ∼ 13.8 Gyr ago (see Wikipedia: Age of the universe; age of the observable universe = 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018) (see Planck 2018: Age of the observable universe = 13.797(23) Gyr) as measured from the probably unreal Big Bang singularity which is the fiducial cosmic time zero (i.e., t=0, lookback time 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018))) and, of course, the fiducial time zero of the Λ-CDM model (the current standard model of cosmology (SMC, i.e., the Λ-CDM model)).

- Just to re-emphasize,

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

produced overwhelmingly most of the

cosmic abundances

of hydrogen,

deuterons,

and helium,

and some significant part of the

cosmic abundance

of lithium-7

and lithium-6.

Image 6 below illustrated the yield of

these elements.

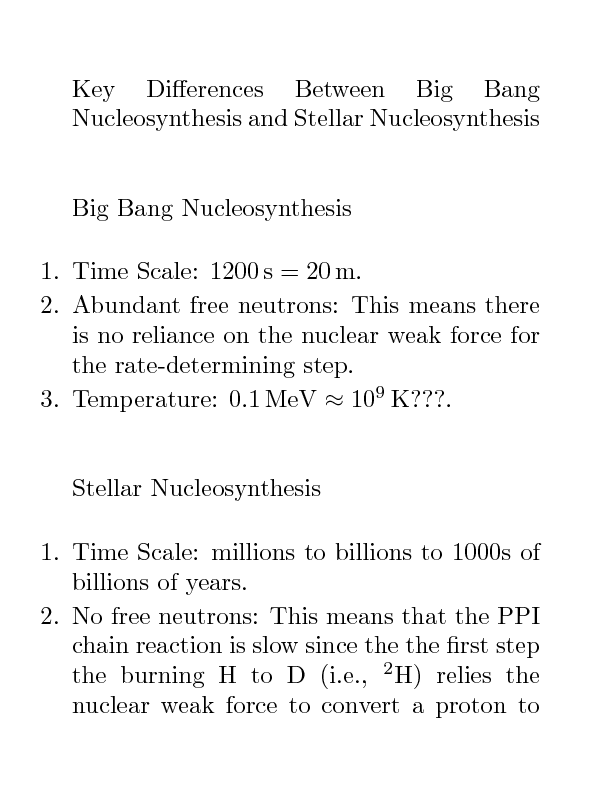

- Image 1 Caption: The nuclear reaction network of Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

For a somewhat more detailed image of the nuclear reaction network of Big Bang nucleosynthesis, see Hyperphysics: Big Bang Nucleosynthesis.

- For Big Bang nucleosynthesis,

the relevant elements,

nuclei,

isotopes,

and particles are the:

- gamma ray (γ): a high-energy photon.

- neutron (n: free n decays to p, half-life

= 610(10)s with uncertainty annoyingly large):

a radioactive nuclide

(i.e., unstable to spontaeous radioactive decay)

when a free particle with

half-life

610.(10) seconds

= 10.17 minutes.

The free neutron decay process is

n → p + e**(-) + ν_(e-bar) ,where e**(-) = electron (AKA negative beta particle) and ν**(e-bar) = antielectron neutrino. - proton (p, H): A hydrogen ion (H**(+)): (stable isotope).

- deuteron (D or H-2): A stable isotope) which is the atomic nucleus of the species deuterium.

- triton (T or H-3: decays to He-3 by beta-minus decay, half-life = 4500(8) days = 12.32(2) Jyr): The atomic nucleus of the species tritium. It is a radioactive isotope with half-life 4500(8) days = 12.32(2) Julian years and radioactive decay product Helium (He-3) (see Wikipedia: Tritium: Decay). The half-life is so long compared to the Big Bang nucleosynthesis era (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m) that the triton is effectively a stable isotope relative to the Big Bang nucleosynthesis era (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m). However, all the primordial tritrium obviously decayed away rapidly in cosmic time and it made ∼ 10 % contribution to primoridial Helium (He-3) abundance (see Image 5 below) which is nearly the modern abundance.

- helium-3 (He-3): A stable isotope.

- helium-4 (He-4): A stable isotope which is much stabler than helium-3 (He-3) which is essentially why it is much more abundant than helium-3 (He-3).

- lithium-6 (Li-6): A stable isotope. Li-6 is very minor product of Big Bang nucleosynthesis, and so its reactions are NOT shown in the nuclear reaction network in Image 1. Big Bang nucleosynthesis predicts only ∼ 2/10**5 of lithium (Li) atoms should be Li-6 atoms (see Johnson 2014, "Big Bang ruled out as origin of lithium-6").

- lithium-7 (Li-7): A stable isotope.

- beryllium-7 (Be-7: decays to Li-7 by electron capture, half-life = 53.22(6) days): A radioactive isotope with half-life 53.22(6) days when it is in UNIONIZED FORM and has radioactive decay product Li-7 (see Wikipedia: Isotopes of Beryllium: Table). In fact, Be-7 radioactively decays by electron capture (p+e(-)→n+μ_e) and this RARELY happens for bare Be-7 nuclei (positive charge +4e). So primordial Be-7 must acquire bound electrons to radioactively decay. Calculations show that the primordial Be-7 radioactively decays to Li-7 (and then adds to the original primordial Li-7 abundance increasing that by a factor of ∼ 10 to the effective primordial Li-7 abundance: see Image 5 below) over cosmic time ∼ 600--1000 years (Cooke 2024, p. 7). The decay time is so long compared to the Big Bang nucleosynthesis era (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m) that Be-7 is effectively a stable isotope relative to the Big Bang nucleosynthesis era (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m).

- The arrows indicate the nuclear reaction

connecting ONE boxed reactant to ONE boxed product with

the other reactant/product being the first/second quantity in the brackets: e.g.,

p(n,γ)D is the same as p + n → D + γ.

The n → p is actually n → p + e**(-) + ν_(e-bar).

The e**(-) (electron)

and ν_(e-bar) (electron antineutrino)

are omitted since they just occur as products and do NOT directly affect

nuclear reaction network again.

- There is a key difference between the

nuclear reaction network

of Big Bang nucleosynthesis

and that of stellar nucleosynthesis:

in Big Bang nucleosynthesis,

there are free neutrons participating

in the nuclear reactions.

Since neutrons are neutral, they have NO Coulomb barrier (i.e., electrostatic force) to overcome to get close enough to other nuclei (which are all electrically charged) in order to undergo a nuclear reaction. The upshot is much faster nucleosynthesis is possible than otherwise such as in hydrogen burning in main-sequence stars. Of course, fast, runaway nuclear burning can happen without free neutrons (e.g., in supernovae), but other special conditions are involved.

- Based on the website

Thespectrum:

Big Bang Nucleosynthesis

(since yours truly

can't find a better source to spit it out right now), the main

nucleosynthesis path in

the nuclear reaction network

(shown in Image 1) is probably

p + n → D no Coulomb barrier, but D is only weakly stable and so photodisintegration creates the deuterium bottleneck. Temperature has to fall low enough to allow deuterium (D, H-2) to survive long enough for further nuclear reactions. D + n → H-3 no Coulomb barrier. T + D → He-4 Coulomb barrier, but the smallest one possible: just 2 positive elementary charges repelling: i.e., p and p.Further nucleosynthesis beyond He-4 CANNOT go by just adding neutrons since the He-4 + n → products and Li-5 + n → products CANNOT survive for further nuclear reactions since He-5 (half-life = 700(30)*10**(-24) s) and Li-5 (half-life = 370(30)*10**(-24) s) are very unstable.

This bottleneck (beyond the deuterium bottleneck) brings nucleosynthesis to heavier nuclei almost to a stop.

Just a little lithium-7 (Li-7), lithium-6 (Li-6), and beryllium-7 (Be-7) get synthesized---and the latter radioactively decays away relatively rapidly as discussed above in Image 1 Features.

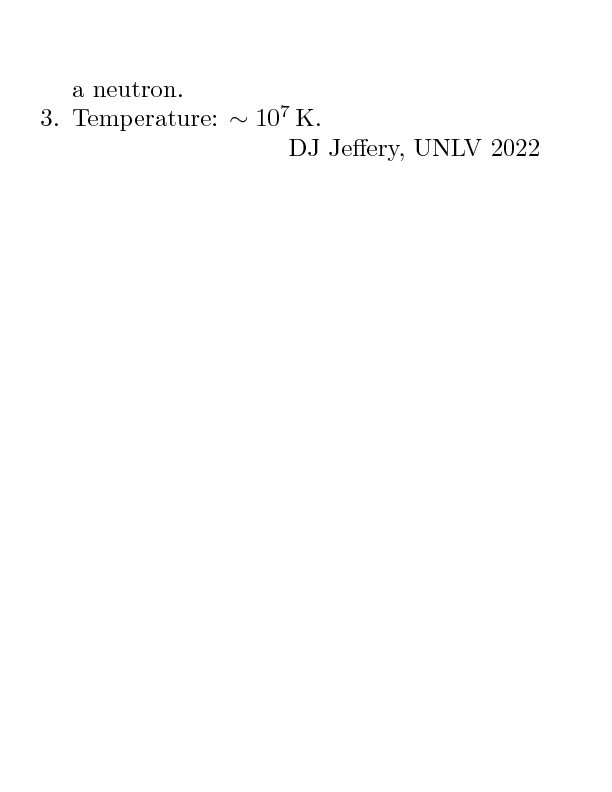

- Image 2 Caption: A table of the nuclear reactions important in Big Bang nucleosynthesis. The table is somewhat more complete than the nuclear reaction network displayed in Image 1.

- A key feature of this table is the reaction that is ABSENT: the

proton-proton (p-p) reaction:

p**(+) + p**(+) → D + e**(+) + ν_e + 1.442 MeV ,where ν_e is electron neutrino (see Wikipedia: Proton-proton chain reaction: The proton-proton chain reaction). This reaction is many orders of magnitude slower??? than any of the shown nuclear reactions and is negligible in Big Bang nucleosynthesis. The essential reason is that an intermediate step is the formation of He-2 (diproton) which is extremely unstable and causes the overall nuclear reaction to have an extremely small cross section. When He-2 (diproton) does form successfully???, it almost immediately??? undergoes beta plus decay to complete the proton-proton (p-p) reaction. In fact, the weak nuclear force is needed to initiate the reaction and that interaction is much weaker than the strong nuclear force. (Note, the above discussion needs improvement, but that requires an improved reference.???) - In the Sun,

the time-scale

for the

proton-proton (p-p) reaction

is 7.9*10**9 yr, whereas the p + D → He-3 reaction has time

scale 1.4 s

(see, e.g.,

Ian Howarth, 2010,

Astrophysical Processes: From Nebulae to Stars, Part 5, Stars II, p. 122).

However, proton-proton (p-p) reaction

is the initial step---and therefore the

rate-determining step---in all

3 branches of

the

proton-proton chain (PP chain)

(i.e., the pp I branch,

the pp II branch,

and the

pp III branch)

for energy generation in the

Sun.

All of stellar evolution

is heavily dependent on the

proton-proton (p-p) reaction, whereas

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

NOT at all.

- Note, the deuterons (D,H-2)

in the Sun's core are all produced in the

PP chain

since primordial

deuterons (D,H-2)

in the Sun's core were all destroyed

very early in the Sun's

main sequence lifetime or before

by the p + D → He-3 reaction.

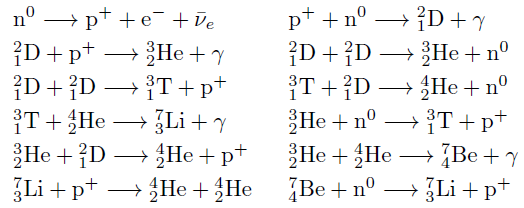

- Image 3 Caption: A log-log plot cosmic temperature (in MeV ≅ 10**10 K) versus cosmic time including the time from the quark era (cosmic time t∼ 10**(-12) -- 10**(-6) s) to the recombination era t = 377,770(3200) y ∼ 1.2*10**13 s (when the primordial photons stopped interacting strongly with matter).

- The

fiducial cosmic time zero (i.e., t=0,

lookback time 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018)))

is the time of the

Big Bang singularity which probably

did NOT happen.

Our best theory is that

the inflation era (10**(-36) -- 10**(-32) s)

happened in the

very early universe

(t < 10**(-12) s)

and then the

observable universe tracked into

a standard

Friedmann-equation model thereafter.

- The cosmic temperature

is the general temperature of the

observable universe.

Before the

matter decoupling era (cosmic time ∼ 12 Myr

∼ 4*10**14 s)

(when matter stopped interacting strongly with

the primordial photons)

(see Hergt & Scott 2024, p. 6),

it was the temperature of all

mass-energy

of all baryonic matter

and primordial photons (i.e.,

conventionally the CMB

even when NOT redshifted to the microwave band: fiducial range 0.1--100 cm)

and after that just of the

primordial photons.

The

primordial photons

cooled

(via

the cosmological redshift

and the decreasing density of photons both due to

the expanding universe)

to create the

cosmic microwave background (CMB)

(in the

microwave band (fiducial range 0.1--100 cm, 0.01--10 cm**(-1))

of

cosmic present = to the age of the observable universe = 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018)

- The primordial photons

have undergone cooling since the

quark era

at least.

Before that we can only extrapolate its behavior.

- The

cosmic temperature

is completely dominated by

relativistic particles

(as far as we know)

which means that

T ∝ 1/a(t), where a(t) is the

cosmic scale factor.

The cosmic scale factor

scales as t**(1/2) before the

radiation-matter equality

(cosmic time t∼ 50,000).

The radiation-matter equality

is the transition time

from the

radiation era

(where

the observable universe's

mass-energy

is dominated by

primordial photons)

to the

matter era

(where

the observable universe's

mass-energy

is dominated by

matter which includes both

baryonic matter

and dark matter).

After the

radiation-matter equality,

the cosmic scale factor

scales as t**(2/3) thereafter.

Thus, T ∼∝ 1/t**(1/2) before the

radiation-matter equality

(t≅ 50,000) and T ∼∝ 1/t**(2/3).

The two behaviors give

straight lines on

the log-log plot with

slopes of, respectively, -1/2 and -2/3.

- The displayed or present in

cosmic eras

in Image 3:

- quark era (cosmic time t∼ 10**(-12) -- 10**(-6) s)

- baryogenesis era (cosmic time ∼ 10**(-1) s) (see also Wikipedia: Baryogenesis)

- neutrino decoupling (cosmic time t∼ 1s)

- Big Bang nucleosynthesis era (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m)

- radiation-matter equality (cosmic time t ∼ 50,000)

- recombination era (cosmic time t = 377,770(3200) y)

- matter decoupling era (cosmic time ∼ 12 Myr ∼ 4*10**14 s) (Hergt & Scott 2024, p. 6)

Note again, the fiducial cosmic time zero (i.e., t=0, lookback time 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018))) is the time of the probably unreal Big Bang singularity of the Friedmann equation models. Λ-CDM model. But though probably unreal, it is a fiducial time zero when running backward the clock of cosmic time.

- Image 4 Caption: A log-log plot of the cosmic time evolution of Big Bang nucleosynthesis era (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m).

- The horizontal axis

is logarithmic

number density

relative to the

number density

of baryons.

Note, the number of baryons

is nearly exactly conserved from about

baryogenesis era

(cosmic time ∼ 10**(-1) s)

(see also

Wikipedia: Baryogenesis) onward in

Big Bang cosmology

until the far future maybe.

- The upper vertical axis

is cosmic time measured

from the

fiducial cosmic time zero (i.e., t=0,

lookback time 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018)).

The lower vertical axis

is cosmic temperature in

MeV ≅ 10**10 K

for each cosmic time.

- Keywords for

Image 4:

baryons,

baryon-to-photon ratio

η = 6.12(5)*10**(-10) = 273.78(18)*10**(-10)*Ω_b*h**2 (Planck-2018, p. 15, Plik[1])

(see Planck-2018, p. 15,

Cooke 2024, p. 7;

Wikipedia:

Big Bang nucleosynthesis: Characteristics:

baryon-to-photon ratio η ≅ 6*10**(-10);

Stackexchange:

baryon-to-photon ratio),

beryllium-7 (Be-7: decays to Li-7, half-life = 53.22(6) days when it is in UNIONIZED FORM)

(see Image 1 Features for the ionized lifetime),

cosmic temperature,

cosmic time (upper axis),

deuteron (D or d, H-2),

helium-3 (He-3),

helium-4 (He-4),

hydrogen (H or p),

lithium-6 (Li-6),

lithium-7 (Li-7),

mass fraction

(related to number abundance),

neutron (n: free n decays to p, half-life

= 610(10)s with uncertainty annoyingly large)

(see Wikipedia:

Free neutron decay: Neutron lifetime puzzle),

proton (p, H),

triton (T or t,H-3:

decays to He-3, half-life = 12.32 Jyr).

- As illustrated in the Image 4,

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

essentially spanned

cosmic time

∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m.

Then it was all over.

- The

primordial cosmic composition (fiducial values by mass fraction:

0.75 H, 0.25 He-4, 0.001 D, 0.0001 He-3, 10**(-9) Li-7)

is the result of

Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

It consists of just light

elements.

Note, the primordial tritium (T, H-3) and beryllium-7 (Be-7) radioactively decayed away relatively rapidly and conbributed to the modern abundances of, respectively, helium-3 (He-3) and lithium-7 (Li-7). See Image 1 Features for a discussion of these radioactive decays.

- Note, post-main-sequence stars

only contribute a small amount

of helium-4 (He-4)

to the modern

cosmic composition

compared to

Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN).

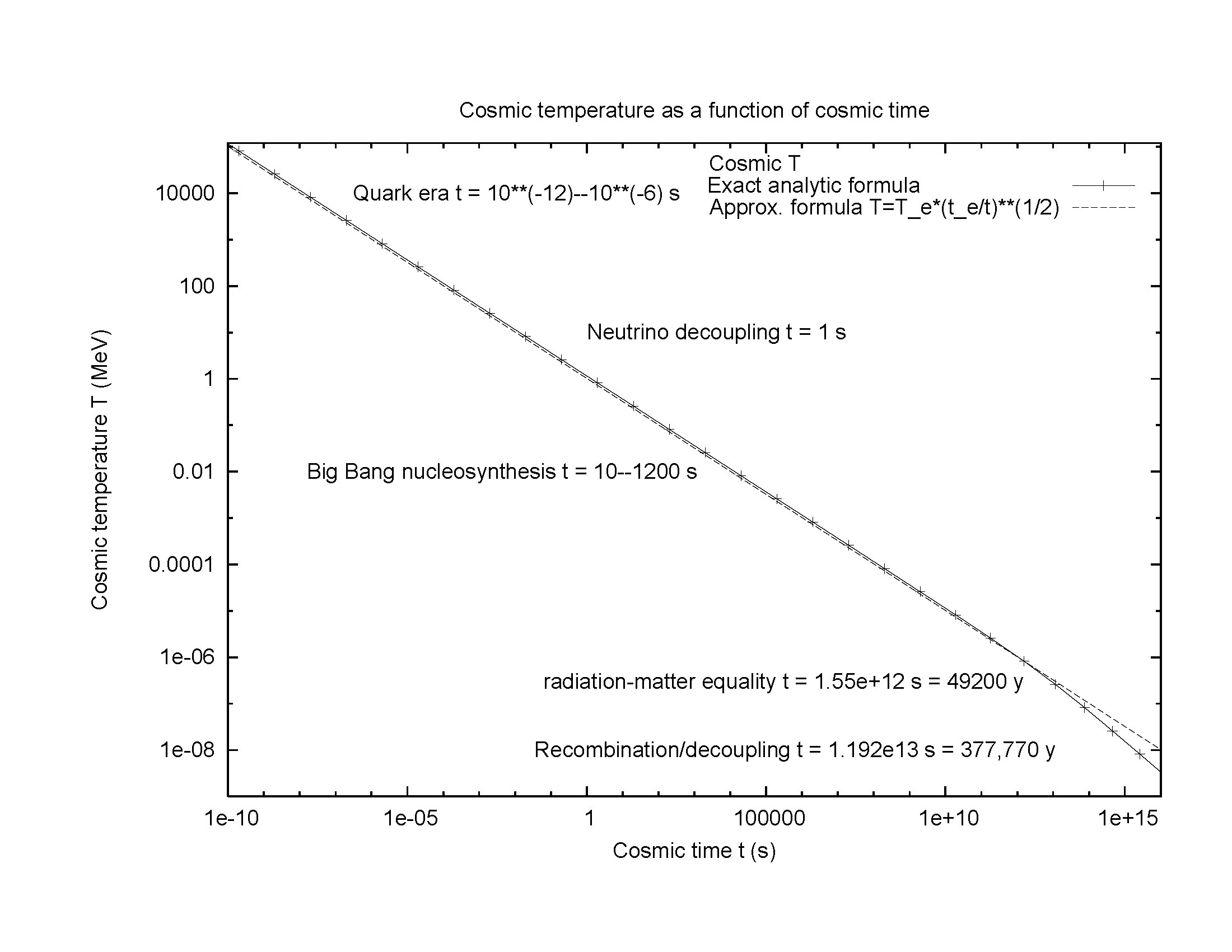

- Image 5 Caption: The key differences between Big Bang nucleosynthesis from stellar nucleosynthesis illustrated.

- Big Bang nucleosynthesis era

(cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m):

This is much shorter than the millions of years to

billions of years of

stellar nucleosynthesis.

- There is an enormous distinction in that

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

has free neutrons

(as discussed above in Image 4 Features)

and stellar nucleosynthesis

does NOT.

- The

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

temperature

is ∼ 10**9 ≅ 0.1 MeV

whereas stellar nucleosynthesis

has a temperature range

∼ 10**7 to 10**10 K

(Google AI question:

Stellar nucleosynthesis temperature range?;

Wikipedia: Stellar nucleosynthesis).

- Another difference of

Big Bang nucleosynthesis from

stellar nucleosynthesis

(omitted in Image 5)

is that

heat energy feedback from the

nuclear reactions

in Big Bang nucleosynthesis

is NOT important in

Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

The universal expansion of the

cosmic photon gas

(AKA cosmic background radiation)

controls the

cosmic background radiation temperature.

In stellar nucleosynthesis,

the heat energy from

nuclear burning is a key ingredient

in setting temperature.

- Image 6 Caption: "This Schramm diagram depicts the predicted primordial cosmic composition of helium-4 (He-4) (purple line), deuterium (D, H-2) (blue line), helium-3 (He-3) (red line), and lithium-7 (Li-7) (green line), as a function of baryon-to-photon ratio η = 6.12(5)*10**(-10) = 273.78(18)*10**(-10)*Ω_b*h**2 (Planck-2018, p. 15, Plik[1]) (see Planck-2018, p. 15, Cooke 2024, p. 7; Wikipedia: Big Bang nucleosynthesis: Characteristics: baryon-to-photon ratio η ≅ 6*10**(-10); Stackexchange: baryon-to-photon ratio) on the lower horizontal axis and equivalently baryon density parameter Ω_b*h**2 on the upper horizontal axis." (Slightly edited.)

- The expression

Schramm diagram

is in honor of

David Schramm (1945--1997),

one of the pioneers of

Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN).

Yours truly met

Dave Schramm long ago.

- The width of the curves

give the

1 standard deviation (1 σ)

uncertainty

of the Big Bang nucleosynthesis

calculation.

- The heights of yellow

rectangles

show the observational constraints on the abundances of the

primordial cosmic composition (fiducial values by mass fraction:

0.75 H, 0.25 He-4, 0.001 D, 0.0001 He-3, 10**(-9) Li-7).

The widths of yellow

rectangles

just show where the observations are consistent with the

calculated

curves (including their widths).

- Note, there is NO constraint for

helium-3 (He-3)

because it CANNOT be distinguished observationally

circa 2025 from the much more abundant

helium-4 (He-4)

(see Cooke 2024, p. 16).

The nuclei

of these two species are very different in behavior, but

their behavior as atoms

in chemistry

and spectroscopy are almost identical.

And remember, we know what the

observable universe is made

of principally from

spectroscopy.

But what you say about hydrogen (H) and deuterium (D, H-2) which are also distinct nuclei but nearly identical in their behavior as atoms? It turns out that they are distinct enough as atoms for spectroscopy to tell them apart.

- The

baryon-to-photon ratio η

is a

free parameter

of Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN)

calculations.

But the baryon-to-photon ratio η = 6.12(5)*10**(-10) = 273.78(18)*10**(-10)*Ω_b*h**2 (Planck-2018, p. 15, Plik[1]) (see Planck-2018, p. 15, Cooke 2024, p. 7; Wikipedia: Big Bang nucleosynthesis: Characteristics: baryon-to-photon ratio η ≅ 6*10**(-10); Stackexchange: baryon-to-photon ratio) is fixed by observations of cosmic microwave background (CMB, T = 2.72548(57) K (Fixsen 2009)) (see (Spergel 2003, p. 11).

Thus, Λ-CDM model and all the observations that are used to fit it, Big Bang nucleosynthesis (cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m) has NO free parameters.

- The photon abundance in

Big Bang nucleosynthesis era

(cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m)

since that is almost constant from that time

to cosmic present = to the age of the observable universe = 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018).

The photons in question are NOT

all photons, but just those

in the

cosmic microwave background (CMB, T = 2.72548(57) K (Fixsen 2009))

whose abundance we can directly measure.

Why is the CMB

photon abundance conserved to high accuracy?

The short answer is

the conditions of the

observable universe

and thermodynamics

require it.

However, we do NOT know the baryon abundance to high accuracy/precision from measurements of the local observable universe.

The upshot is that the high accuracy/precision determination of baryon-to-photon ratio must depend on the cosmic microwave background (CMB, T = 2.72548(57) K (Fixsen 2009)) (see (Spergel 2003, p. 11).

- The fit to observations

of free parameter free

Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN)

is considered excellent overall as seen in

Image 6

- The Helium-4 (He-4) fit is good.

- The deuterium (D,H-2) fit is amazingly good.

- There is NO fit for helium-3 (He-3) as of circa 2025 for reasons as discussed above.

- The lithium-7 (Li-7)

observed in certain low metallicity

main-sequence stars

has been considered the best

observational abundance for

primordial Li-7.

However, as

Image 6 shows, this observational abundance is ∼ 1/3

of the prediciton of

BBN

(Wikipedia:

Cosmological lithium problem: Observed abundance of lithium).

The discrepancy, called the

cosmological lithium problem,

is a significant concern for

BBN.

However, circa 2025

is thought likely that unaccounted-for

lithium burning

in stellar nucleosynthesis

occurs in the observed

low metallicity

main-sequence stars

is the cause of the discrepancy and NOT

BBN

(Cooke 2024, p. 20).

A key point is that despite the discrepancy,

the agreement is between observation and prediction is still

order of magnitude good.

- Now the

strong evidence for

BBN gives

strong faith in the determined

baryon abundance.

However, this means that dark matter CANNOT be baryonic matter. In fact, the baryon fraction (ratio of baryonic matter to baryonic matter plus dark matter) is ∼ 1/6 = 16 % for observable universe (Ci-27) as we know from galaxy rotation curves and other evidence (see Galaxies file: galaxy_rotation.html; Galaxies file: galaxy_rotation_curve_cartoon.html).

Besides being ruled out as baryonic matter by BBN, dark matter is also ruled out nearly by being very, very dark. It is believed that if dark matter was baryonic matter AND as abundant as it is, then it would emit electromagnetic radiation (EMR) that is obviously coming from baryonic matter. Many theories predict dark matter does produce some EMR, but NOT nearly as much as the same amount of baryonic matter.

- To complement Image 6,

the predictions of

primordial cosmic composition (fiducial values by mass fraction:

0.75 H, 0.25 He-4, 0.001 D, 0.0001 He-3, 10**(-9) Li-7)

from Big Bang nucleosynthesis

are compared to observations below in

Table: Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN) Predictions and Observed Primordial Cosmic Composition.

Notes:

Table: Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN) Predictions and Observed Primordial Cosmic Composition _____________________________________________________________________________ Element BBN Observed Quantity _____________________________________________________________________________ He-4 0.2485(20) 0.2453(34) mass fraction D (H-2) 2.692(177) 2.527(3) D/H, x*10**(-5) He-3 9.441(511) ≥ 11(2) He-3/H, x*10**(-6) Li-7 4.283(335) 1.58(35) Li-7/H, x*10**(-10) _____________________________________________________________________________- The values are from Bertulani et al. 2022, p. 5. Note, these values are representative. Different research groups are always producing slightly updated, slightly different values.

- The "elements" (i.e., species) in the table are deuterium (D, H-2), Helium (He-3), helium-4 (He-4), and lithium-7 (Li-7).

- Helium (He-3) and helium-4 (He-4) CANNOT easily be distinguished observationally as they are chemically and spectroscopically nearly identical since they are both isotopes of helium (He). So the lower limit on the cosmic He-3 abundance given in the table is probably very uncertain.

- The Anthropic Principle Aspect:

There is an anthropic principle aspect of Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN).

If the strong nuclear force were just a bit stronger than it is, the Big Bang would have nuclearly burned all the hydrogen into helium (see Wikipedia: Anthropic principle: Anthropic observations: scroll to the 3rd paragraph).

Without hydrogen, there would be NO water and NO hydrocarbons, and therefore would be NO life as we know it.

Life as we know it uses liquid water as the medium for all its chemical reactions and there is NO substitute that we think likely.

-

Note, human body water is on average ∼ 60 % by

mass

(Wikipedia: Body water: Location).

We evolved to live outside of the ocean, but only by having an ocean within.

You can take the buoy out of the ocean, but you can't take the ocean out of the boy.

Also long-lived stars are probably needed for life as we know it and probably could NOT exist without forming as mainly hydrogen.

The upshot is that the existence of hydrogen constrains the strong nuclear force to be NOT much stronger than it is.

This upshot leads to an anthropic principle argument for the multiverse paradigm since there is NO known fundamental (and human-independent) reason making the strong nuclear force just as strong as it is. With NO known fundamental (and human-independent) reason, it seems plausible that the strong nuclear force strength is somehow randomly chosen. But if the strength is randomly chosen, there is some distribution of strengths and all of these strengths could be chosen elsewhere. Elsewhere could be different pocket universes in a multiverse (which may be an eternal inflation universe) and its strength in our pocket universe is below the upper bound needed for hydrogen to exist since entities needing hydrogen are in our pocket universe. So a multiverse is somewhat plausible. However, remember that all anthropic principle arguments it seems lead to endless disputes about their validity.

- The

Big Bang nucleosynthesis era

(cosmic time ∼ 10--1200 s ≅ 0.17--20 m)

began at ∼ 10 s after the

fiducial cosmic time zero (i.e., t=0,

lookback time 13.797(23) Gyr (Planck 2018)))

of the Friedmann equation (FE) models.

At cosmic time ∼ 10 s,

the cosmic temperature

had fallen sufficiently low that

protons and

neutrons

were NO longer being created by

pair creation

by photons

(since the photons NO have

the energy as the

required

photon energy E=hν as

cosmic temperature falls

to create such massive particles)

and nuclei

were NO longer being destroyed by

photodisintegration

(since the photons NO longer have

the photon energy E=hν as the

cosmic temperature falls

to destroy nuclei).

Also by some asymmetry in the early part of

early universe

(cosmic time (10**(-12) s -- 377700(3200) y),

the bulk antimatter had vanished

(Wikipedia:

Antimatter: Origin and asymmetry;

Wikipedia: Baryogenesis).

So there was NO longer antimatter

to complicate

Big Bang nucleosynthesis

at cosmic time ∼ 10 s.

-

Images:

- Credit/Permission: ©

User:Pamputt,

2019 /

CC BY-SA 4.0.

Image link: Wikimedia Commons: File:Main_nuclear_reaction_chains_for_Big_Bang_nucleosynthesis.svg.

-

Credit/Permission:

User:Cmbant,

2011 /

Public domain.

Image link: Wikimedia Commons: File:Primordial_nucleosynthesis2.png.

- Credit/Permission: ©

David Jeffery,

2019 /

Own work.

Image link: Itself.

- Credit/Permission: ©

Chris Mihos,

before or circa 2016 / None.

Image link: nucleosynth_fig.jpg.

Image link: Placeholder image alien_click_to_see_image.html. The Li-6 in nucleosynth_fig.jpg looks way too high since accurate Big Bang nucleosynthesis predicts only ∼ 2/10**5 of lithium (Li) atoms should be Li-6 atoms (see Johnson 2014, " Big Bang ruled out as origin of lithium-6"). Creators of this particular Big Bang nucleosynthesis plot may have articifially increased the cross section of Li-6 to match the observed abundance in modern observable universe. The discrepancy between the Li-6 abundance from (accurate) Big Bang nucleosynthesis of observed abundance is part of the cosmological lithium problem which we discussed above. - Credit/Permission: ©

Tsung-Han Yeh,

Keith A. Olive (1956--),

Brian D. Fields

2023

(uploaded to Wikimedia Commons

by User:Pamputt,

2023) /

Creative Commons

CC BY-SA 4.0.

Image link: Wikimedia Commons: File:Universe-09-00183-g004.png.

See also Credit/Permission: © Chris Mihos, before or circa 2016 / None.

Image link: nucleosynth_fig.jpg.

- Credit/Permission: ©

David Jeffery,

2023 /

Own work.

Image link: Itself.

Former image: Credit/Permission: © Ann Zabludoff???, before or circa 2012 / None. The now dead link Atropos: Primordial Nucleosynthesis versus Stellar Nucleosynthesis is very enlightening, but it completely omits the enormous distinction that Big Bang nucleosynthesis has free neutrons (as discussed above) and stellar nucleosynthesis does NOT. - Credit/Permission: ©

User:Paleo2,

2020 /

CC BY-SA 4.0.

Image link: Wikimedia Commons: File:Schramm plot BBN review 2019.png.

File: Cosmology file: big_bang_nucleosynthesis.html.